The long black line

A street-legal car runs for a world speed record

by Greg Raven

Autotech magazine

March 1988

photography by David Fetherston

"No stops signs

AC/DC,

Speed limits

Nobody’s gonna slow us down."Highway To Hell

There is amateur racing and then there is amateur racing. The Bonneville Nationals are amateur racing in the best sense of the word, a reminder of antediluvian times. Speed Week at Bonneville is the last of the big-time amateur racing events … the only one of its kind.

The 1987 Bonneville Nationals was somewhat of a landmark, coming as it did 50 years after the first-ever pilgrimage to Wendover, Utah, by racers bringing nearly every imaginable type of racing machine in attempts to beat the clock. They have been at it ever since. This year was also the 39th National Speed Trials run by the Southern California Timing Association, the same folks who run similar events on the dry lakes in the desert at El Mirage. The cleanliness and coruscating brilliance of the salt flats seem a far cry from the dust of the dry lakes, however. For that matter, the salt flats are a far cry from just about anything else you’ve ever experienced, enough so that for some people it takes a day or two just to stop referring to the salt as snow

or ice.

It’s a two-hour drive west from Salt Lake City to Wendover, Utah, but it seems longer; at the half-way point, you can already see the mountains against which nestles the edge of the salt flats where the race is run. The distances are so vast that you always think you are seeing something you are not, so when you get to the 30,203 acres of land the Bureau of Land Management refers to as having prime crust (up to 6 inches of pure salt over a salt and clay substrate), the salt flat looks smaller than it is. Once you are out on the salt, time and space become plastic; now changing, now static, simultaneously expanding and contracting. Reality maintains a low profile, but it’s there; it is much easier to appreciate the peace and quiet when you have plenty of food, water, and fast transportation. On foot and with no canteen, this would be Hell itself.

It doesn’t take much of a push to get most people to put their lives on hold for a week, grab the tanning oil, and head for the salt flats. This year the nudge came from Denny Kahler, of Kahler’s Porsche/Mercedes Service in Dublin, California. Denny narrowly missed having his 1974 Porsche 911S ready in time to take part in last year’s Speed Week. This year the little drop-windshield coupe was more than just ready, with a twin-turbo 2-liter motor in the engine bay and a 3-liter motor in the transporter, Denny was hunting for at least one and possibly two records in this, his first time out.

Number 107 will make its first attempt with a 2-liter engine built on a 1965 case, using a 2-liter counter-weighted crankshaft around which the 2.2-liter rods have been bolted and then welded to keep them from coming apart at 8,500 rpm. Stock 2-liter aluminum barrels with cast iron inserts contain the heavily modified Arias forged pistons. Mated with the modified and match-ported early 911S 2-liter heads running 934 camshafts, the compression ratio has been set at 7.3:1.

Ignition is left to breaker points and single spark plugs, with an MSD capacitive-discharge unit in between to handle both spark advance (the stock Bosch advance mechanism is locked down) and boost retard. The turbochargers blow through a huge custom-fabricated intercooler that all but conceals the motor from view. Internal volume of the intercooler? Who knows? Who cares? Don’t have to worry about turbo lag out here,

explains Denny. The turbos themselves are the same as those used on the Ford SVO, with the integral wastegates controlled by a Boostpak Turbo Management System. An exhaust oxygen sensor read-out sitting atop the Boostpak controller indicates whether the engine is running rich or lean.

In the best amateur tradition, we have no idea what kind of horsepower the engine puts out or what the torque curve is. If we did we might not have bothered to show up. The Bosch mechanical fuel injection was originally programmed to run a 2.2-liter normally-aspirated motor. By connecting a separate turbo wastegate to the cold mixture enrichment adjustment, Denny hopes to trick the pump into delivering enough fuel even under boost.

The dropped windshield makes the Porsche look like an oversized watermelon seed that has been painted emergency-vehicle red. Without wind tunnel testing, all we know for sure is that the frontal area has been reduced — the coefficient of drag could be anything. One immediate change due to the dropped windshield is a class change; instead of running as a Grand Touring (GT) car, Kahler’s street-legal streaker will run in the Modified Sport (MS) car class.

Two-liter normally-aspirated engines run in the G engine class. With the turbocharger, the classification is bumped up by two, putting it the E engine class. The E/MS class is virgin territory for which the world record can be set with any run over 170 mph. Setting the record is not on Denny’s mind, however. He wants 200 mph and he wants it bad. Denis Waitley could learn something from observing Denny talk about what the car will do when he finally gets to run it.

One thing Denny’s concentration level doesn’t have much effect on is the weather. Sporadic rainstorms have left the salt soaking wet, and although the prediction is that the salt will be dry enough to run on, nobody knows for certain.

Sunday Qualifying

The first impression is that they must be giving away free money. Between logistical problems caused by the dampness and the number of contestants, early-birds are the only ones with even a glimmer of hope of making two runs.

We made the critical mistake of waiting until the sun was up until driving from nearby Wendover to the track. Denny’s confidence remains high as the wait stretches farther and farther into the day. When our turn final comes, the Porsche leaps off the line with visions of 200 mph dancing in Denny’s head.

As we head down the return road in crewmember Bob Graham’s Ford van, we hear over the CB radio that Denny’s speed was 98.551 — less than half of the magic number. It is too late in the day to hope for another run, so it’s back to the pits to determine what is wrong.

Monday Qualifying

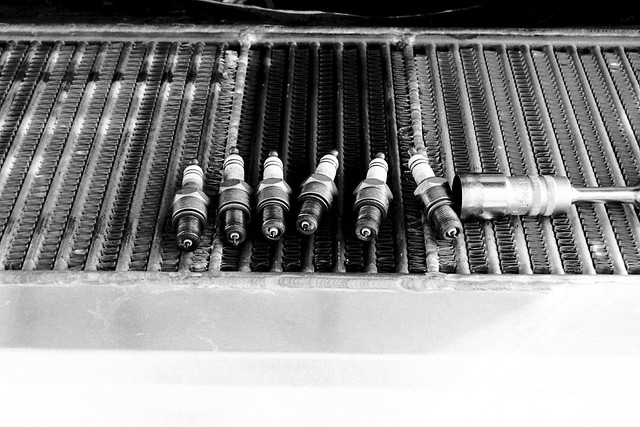

With no way of adequately testing components or equipment combinations, we are reduced to examining the spark plugs and then bench-racing what we find.

The only solid information we have is that plugs one through five have a nearly perfect tinge of coloration to them while the porcelain on plug six is as white as the salt beneath the Yokohama 205/55ZR16 tires. We switch injectors on cylinder six and hope for the best.

Cars from Sunday’s runs that qualified for record runs start off the day performing their two-way runs, with the track closed to the rest of us. Along with everybody else, we are waiting in line when qualifying reopens in the afternoon.

Denny feels that the car was running well at slower speeds but that it runs out of gas

at the top end. He gets a chance to test his theory by adjusting both the boost and the fuel delivery with one hand while the other hand tries to keep the car centered on the black line that runs the length of the track. This ad hoc fiddling nets him a speed of 113.636. Plug number 6 is still running lean and clean. Unfortunately, one run is all there is time for again today.

Adjusting the mixture and boost on-the-fly has shown us the light at the end of the tunnel, however, and Denny is eager to get a better view. Instead of heading back to the pits right away he points the car toward the short test area to the east of the pits for a couple of unsanctioned power runs. Fortunately, none of the officials notices and no one complains, and Denny begins to find the elusive combination that he hopes will push him over the double-century mark.

Tuesday Rain

And more rain. The evening’s thunderstorm was spectacular but by morning the access road leading to the track is bracketed on both sides by deep water, the pits are submerged, and the track itself is under one-half inches of water. Some of the competitors head for home.

We might have, too, if Bob’s van had been working. Instead, we took advantage of the day off get the necessary parts and make repairs. Slack times are filled with speculation and more bench-racing. By midnight the rumor is that tomorrow the track will be dry enough to resume qualifying.

Wednesday Qualifying

Denny has lost none of his confidence in the car’s ability to reach 200 mph, but it’s no secret that we need some more runs to get the car sorted out.

The day dawns bright and almost cloudless. A warm breeze has been blowing since early Tuesday evening and the hope is that the evaporative process has been working overtime to reclaim the track. After a quick breakfast, we drive out through a gauntlet of brine 8 inches deep to get to the pits. Even the survivors will be fighting the battle against rust for years to come.

The track is indeed wet. Even though the officials have cordoned off the really soggy end of the track, the salt at the launch point looks to be no more than a couple of millimeters above the water table. Not until after noon is the track declared fit for racing.

Our first run is good. Speed in the first timed mile is 152.104, increasing to 155.005 in the second. We’re ecstatic. Denny is pensive. His Category E driving license allows only speeds of 149 or lower. By breaking out of his driving license category there is a possibility of disqualification. We find a sympathetic official who signs him off for a Category C license, obviating the need for the Category D licensing run.

Back in line and out with the spark plugs. Number six still shows naked porcelain in contrast to the other plugs, which are all reading about the same. With the rain-shortened line comes the possibility of getting in some more runs. Denny is more optimistic than ever. It feels like there is plenty (of power) left,

he nods eagerly. As a stop-gap, we put a colder plug in hole number six.

The possibility becomes a reality and we get our second run of the day. Over the CB comes good news; first mile at 170.648 mph, the second mile at 172.894 mph. With the record sitting at 170.000 mph, we have qualified for Thursday morning’s record run.

Denny has the bit between his teeth now. Two hundred mph seems but a breath away. Never mind that he just qualified for the world speed record in his category. He wants to step into the box and swing for the fences. If the motor goes away, we’ll simply put in the 3-liter and try again Thursday afternoon. As far as he’s concerned it’s now or never. At the end of the run, the engine had gone flat, as if the fuel supply had abruptly been shut off. He killed the ignition immediately, but at 6,700 rpm it doesn’t take much time to do some real damage. If the engine has been hurt, Denny wants to find out now instead of during a record run. That way, we’ll have all night to work on the motor, if need be.

Back in line for the last time we pull the plugs and find nothing has changed. It’s time for more decisive action. Neither changing the fuel injector nor running colder plugs has had any effect. It must be the mechanical injection pump itself. Although supposedly calibrated by one of the few firms with the knowledge and equipment to carry out the delicate adjustment procedure, now it appears to be the Achilles heel that could cause the whole effort to come up lame.

Taking a deep breath, we remove the cover from the side of the injection pump. Denny and I stare into the mechanism, actuating the plungers and moving the racks back and forth in an effort to second-guess the Bosch engineers who designed it. The whole thing seems ludicrous, considering how far removed our installation is from the intended application.

Half an hour of OJT later, we agree that we finally understand all we know about the internal workings of the injection pump. With that settled, Denny recommends turning the plunger adjustment to the left. My calculations require the adjustment should be moved to the right. Back into ponder mode. Denny finally moves the adjustment to the right and slaps the side cover on, ready to go racing.

Cylinder number six gets its original heat-range plug back, and the overall enrichment adjustment gets a couple turns, just in case that flat spot was the motor going lean on the big end. As the car pulls away from the line we can hear that the motor is running fat. It might be set just right for the top end but if it runs too poorly at the low end it will never get the speed it needs on the rain-shortened track. The announcer gives us the disappointing news … 143 mph. The plugs all show a too-rich mixture.

Thursday Record Run

The day dawns crystal clear with the same warm breeze blowing as the night before. For the third consecutive day, temperatures have hovered in the low 70s, making perfect conditions both for making record runs and for sun-loving crewmember Jim Gaeta, the man with far and away the best tan in the State of Utah. Here and there are signs that the water level is coming down but there is still an awful lot of it left. In the pits we drain the fuel tank (a requisite), remove the outside rear-view mirror, lean out the fuel injection, and replace the number six spark plug again.

That done, we get into the fuel line for our allotment of blue 117 octane gasoline, then it’s off to the track. Waiting in line for our turn at the record runs affords us a time of relative tranquility with which to enjoy the surroundings.

The miles of salt and timeless quality of the area are stunning, but the people and cars that attend the Bonneville Nationals are really what make this event a very special one. There is no litter, no pushing or rudeness in line, none of the massive egos you see in other forms of racing, and no slavish obeisance to particular cars, personalities, or entrenched hierarchies. There are still rules and officials, but for the most part, what you have is a big bunch of friendly folks who are intelligent enough to look after themselves and have fun doing it.

Denny’s still not satisfied with the speed he’s getting, however. Cars running under 200 mph must share the two right lanes. The faster cars have the left lane reserved for them. He wants to use the left lane.

Waiting time is also strategy time. From the way the car feels, when it is too rich down low it is too lean at high rpm; when it is too lean on the bottom it is too rich at high rpm. The fuel injection pump simply can’t cover all the bases, leaving the fuel curve miles from the boost curve. Only Denny’s in-flight adjustments are keeping the two within a reasonable distance of each other.

During the run, it’s all Denny can do to make the adjustments based on what he feels in the seat of his pants, let alone keep track of what he’s doing. This run, we note the settings at the launch so they can be compared with the settings at the end of the run: wastegate set at 12, enrichment at 2.5.

With three cars still ahead of us in line, I take off for the two-mile mark so I can hear how the engine sounds during the pass. Standing out in the sun-washed salt with miles of white stretching away from me in all directions, it seems like an eternity before I finally see a small red blip solidifying out of the heat distortion in the air. This time, there is no stumbling or misfiring; the engine is pulling strongly, the note of the engine rising smoothly as the car accelerates towards terminal velocity. Once past me, when the Doppler effect should come into play, the sound continues to rise, telling me that the little 2-liter is still accelerating. Speed on the first run: 182.898 mph. Plug number six is perfect, exactly matching the coloration of the other five. Our black box engineering worked. Now we’re getting somewhere. Denny asks how the engine sounded, but he already knows it sounded good.

He’s now more convinced than ever that there’s a 200 mph run waiting there for the taking. The speeds are the average of the speed of the vehicle over the measured mile. Based on the transmission ratio, final drive, and tire size, the tachometer says we are doing close to 200 mph at the end of the run. We simply need to get there a little sooner.

While qualifying runs are all done running the same direction, record runs must be done going both ways to negate the effects of wind, continental drift, etc. All the qualifiers make their pass going one way then remain at the far end of the track so that all return passes can be run at once. Our pass over, we line up at the other end of the track and wait for the rest of the qualifiers to complete their first runs.

Behind us in line is the beautifully prepared number 333 Varni, Walsh, Walsh, Cusack AA/GR highboy (later the winner of the 1987 award for Best Appearing Crew & Car). After spinning twice on the course at speeds nearing 200 mph and losing an engine in a big way, number 333 finally posted a 222.783 qualifying time against a 220.166 record. One of the crewmembers periodically glances over at a panel of gauges mounted in their tow vehicle and shakes his head. Lot of air. Lot of air.

There certainly is. Between the relatively low temperature and other atmospheric conditions, air density at the 4,214-foot elevation of the salt flats is high, meaning fuel systems can be run richer so engines make more power. Others have discovered this, too, because as the morning wears on the far end of the track begins to get crowded. Lots of competitors have qualified for record runs. The rain might have caused some logistical problems, but the salt is as fast as ever.

With a strong first pass behind us, the waiting for the return pass becomes interminable. Suddenly the line is moving and we are almost caught unprepared. Roll up to the line, take off the car cover, put on the driving suit (still damp with the sweat of the first run), strap in, and go. Running alongside the track on the return road, we can see the number 107 Kahler’s Porsche Service car, nose to the ground, sniffing the black center line like a berserk mechanized bloodhound on a scent. Over the noise of the open window, the exhaust note sounds sweet sweet sweet.

The squawk over the CB is even sweeter. Second pass speed: 184.577. Average speed: 183.737. A new world’s record.

Before anything else can happen, however, the car must go into impound and have the engine torn down for inspection. If the engine has too much displacement for our class we will be disqualified.

Prior to the engine teardown, the car must pass a visual inspection. The inspector walks over, checks that the fuel tank is still safety wired shut (signifying that no fuel has been added since the morning fuel fill-up), then casts a wary eye over the rest of the car.

One thing you have to understand about Bonneville is that although the mix of vehicles looks like something you might see in the parking lot of a bar in a George Lucas space extravaganza, only a small percentage of the cars there is based on foreign vehicles. Beyond a twin-turbo Citroen and a couple of Volkswagens, nearly everything else is American. This Porsche thing could hardly be more alien.

So the inspector looks at the roof and writes us in as a Production Coupe. Denny interrupts to point out that with the lowered windshield we should be in Modified Stock. The inspector looks again at the roof. I thought they all looked like this,

he says. No, Denny points out, the windshield is lowered. Can’t chop the top in the Modified Stock category,

says the inspector. I’ll have to put you in with the Competition Coupes.

I turn to Denny, expecting him to say something like, The rulebook says …

or We already got an okay on this,

but instead he says, I’ve been meaning to talk to you about that.

This doesn’t look good. More than a year of hard work, four days of concentrated anxiety, a pair of back-to-back record speed runs, and now he is just getting around to asking them if the car is legal?

By this time another official has wandered over to check out the situation. To the assemblage, Denny points out that he didn’t really lower the roof … he lowered the windshield and the roof kinda followed. After some rather negative-sounding discussion, one of the officials claims he vaguely remembers speaking with Denny about this over the phone. He turns and walks off, satisfied that the car is properly classified. The other officials look after him for a moment, then shrug and pencil us in for the E/MS class, right where we wanted to be.

Back in our pit area an official wires the engine to the body and crimps a tamper-proof seal around it. This allows us to tear down the engine on our own while keeping the officials satisfied that the engine they eventually inspect is the same one with which we made the run. Jim Gaeta, Bob Graham, Denny and I start dismantling the right side of the engine so the officials will be able to measure the bore and stroke. Tearing the engine down is quick work, and the official word is 66 mm stroke and 80 mm bore, 1,991 cc, which when turbocharged puts us in Class E. The record is ours.

The rest of the day is spent putting the motor back together. Denny is confident there is a 200 mph run in there, and he doesn’t mind breaking the engine to find it. By sundown, we have the reassembly fairly far along, but there are still several hours of work that need to be done tomorrow.

Friday Qualifying

The engine is back together and once again we find ourselves waiting in line. Because of the successful record run yesterday there is a pleasant lack of tension in our group. All except for Denny, who wants to go home with that big number on a timing slip. On the last two runs, the car felt solidly placed on the track, so — for now — there is no concern with the car becoming airborne due to excessive lift.

The car pulls away from the start sounding as it did for the two record runs, but just before the two-mile mark the engine suddenly falls silent. A bad noise from the engine, later diagnosed to be a failed piston pin in number two cylinder, brings an end to the 2-liter’s chances of joining Bonneville’s 200 MPH Club.

Epilogue

Due to the strong showing by the number 107 Kahler Porsche, the team was unexpectedly invited back for a special invitational run three weeks after Speed Week. With no time to freshen up the 2-liter, Denny installed the twin-turbo 3-liter motor behind a 4-speed Turbo gearbox he had received in trade from a customer who had upgraded to a 5-speed Ruf ’box. Instead of the stock 0.625 fourth gear, a 0.687 fourth had been installed, but that was still high enough to allow a 200 mph run at just under 7,700 rpm.

Right out of the box the car seemed to be running well. The tach needle swung around the dial to 7,700 rpm effortlessly, then kept right on going up to 8,000 rpm. According to mathematics, that should have worked out to be 209 mph.

The timing lights came up with a different number: 175 mph. It sounded like the title of an Earl Stanley Gardner detective novel, The Mystery of the Missing MPH.

After a few minutes of police work, the missing mph were found but the story didn’t have a happy ending. The 4.22:1 stock ring-and-pinion with which Denny had done his calculations had at some point been replaced with a 5.13:1 ring-and-pinion. There was no way that motor could be spun tight enough to match the E class record, let alone go over the top in D class.

No, it wasn’t very professional. And no, the car didn’t go like gangbusters and break every record in the book. But an amateur team, competing in an amateur race with a street car, set a new world’s speed record.

And there’s always next year.